price

250 TEZ97/108 minted

5 reserved

Project #19437

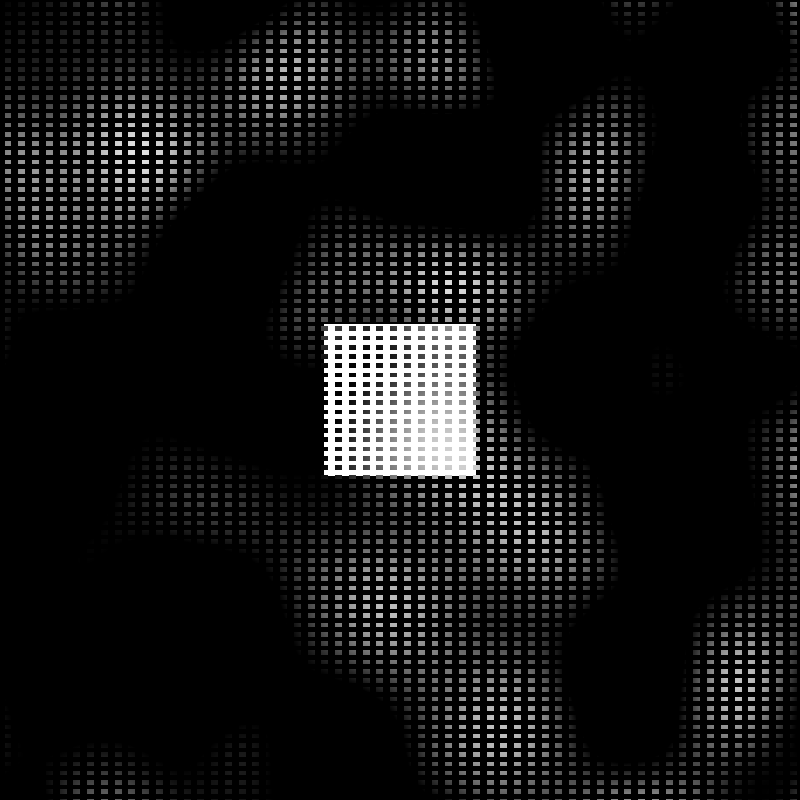

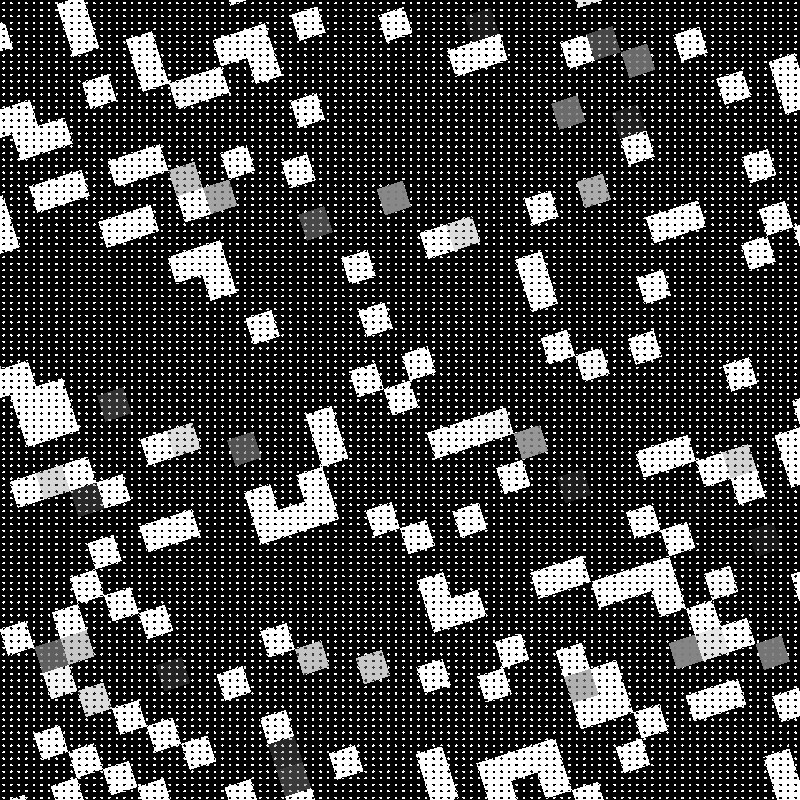

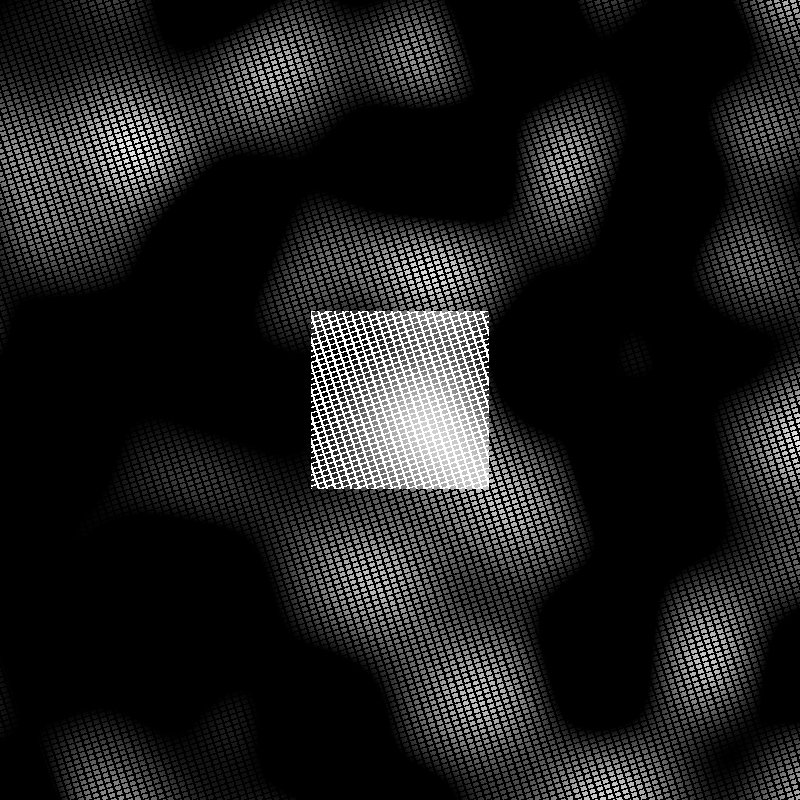

Ryoanji (龍安寺, The Temple of the Dragon at Peace) is a Zen temple located in Kyoto, Japan. The Ryoanji garden, considered the grail of kare-sansui ("dry landscape"), a type of Japanese Zen temple garden. Kare-sansui features distinctive larger rock formations arranged amidst a sweep of smooth pebbles raked into patterns that facilitate meditation.

If meditation is of the mind, then generation is a meditation of the machine. Generations of my coding asserted or not, of the gardens, ease mediations, in a sense of the infiniteness and impermanence of the generated.

Given the reality of physics, rearrangements of Ryoanji is not feasible. As John Cage composed his Ryonaji with chance, pencil and paper. I recompose Ryoanji exploring the limits and boundary of generative art in code. An explorations of meditation.

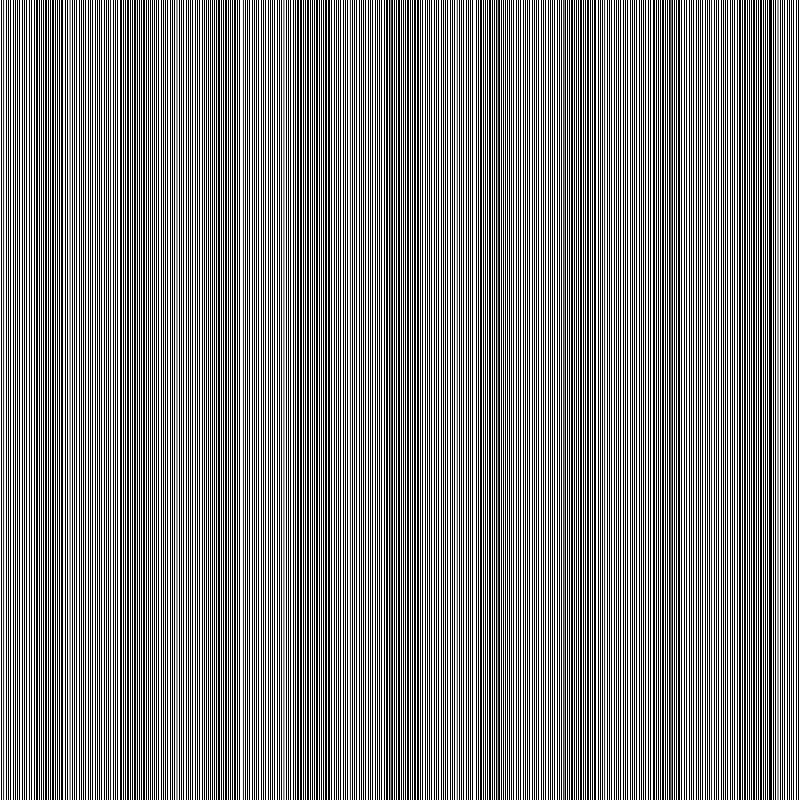

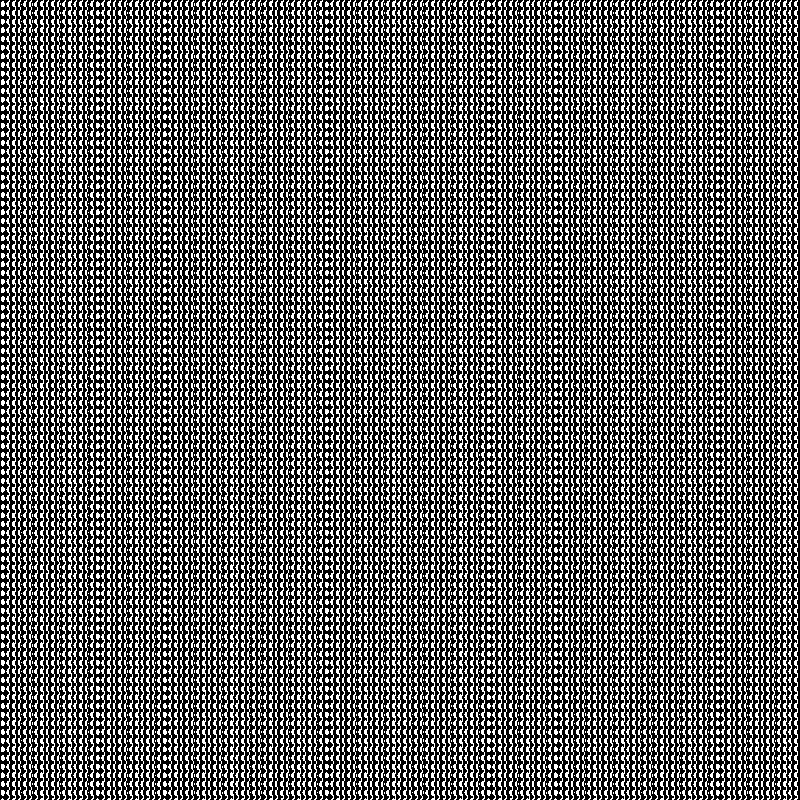

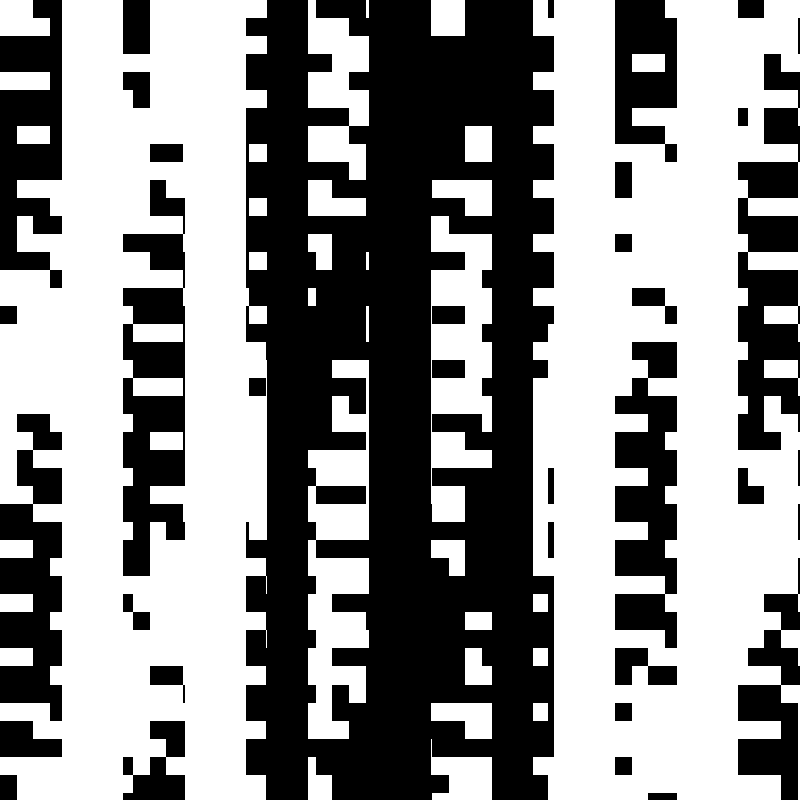

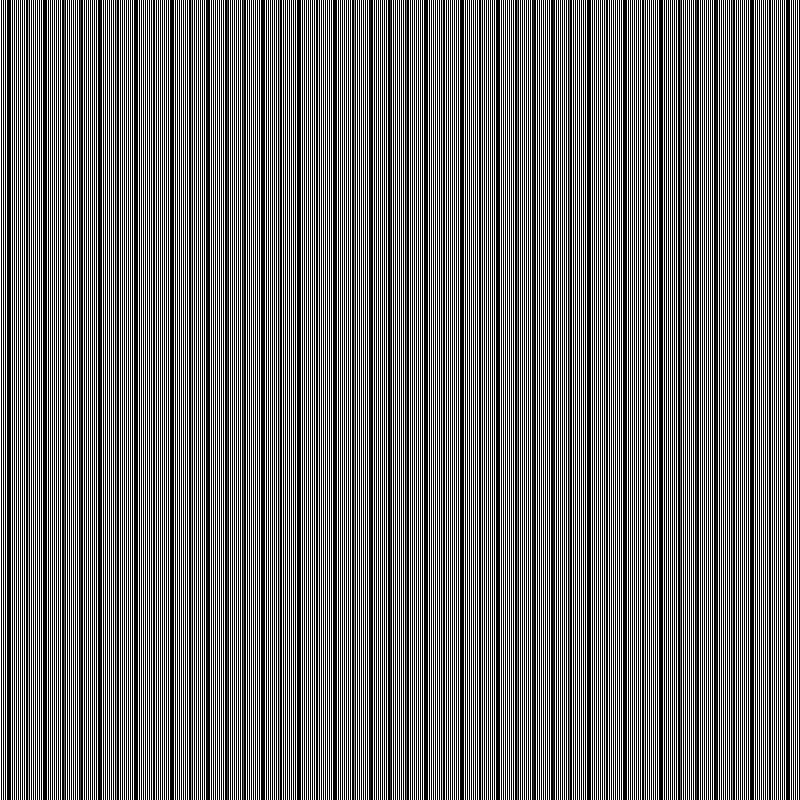

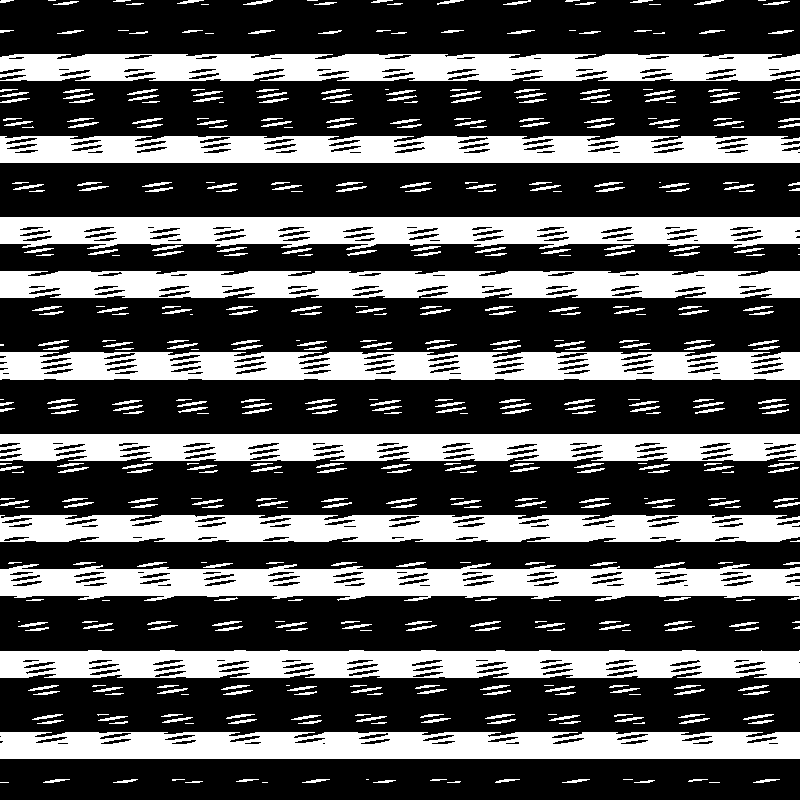

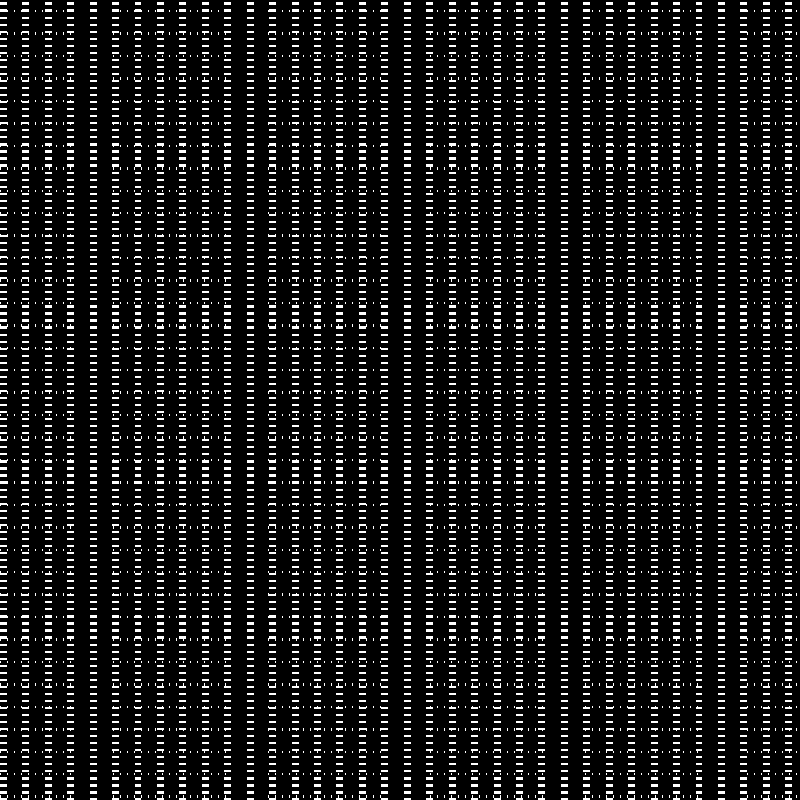

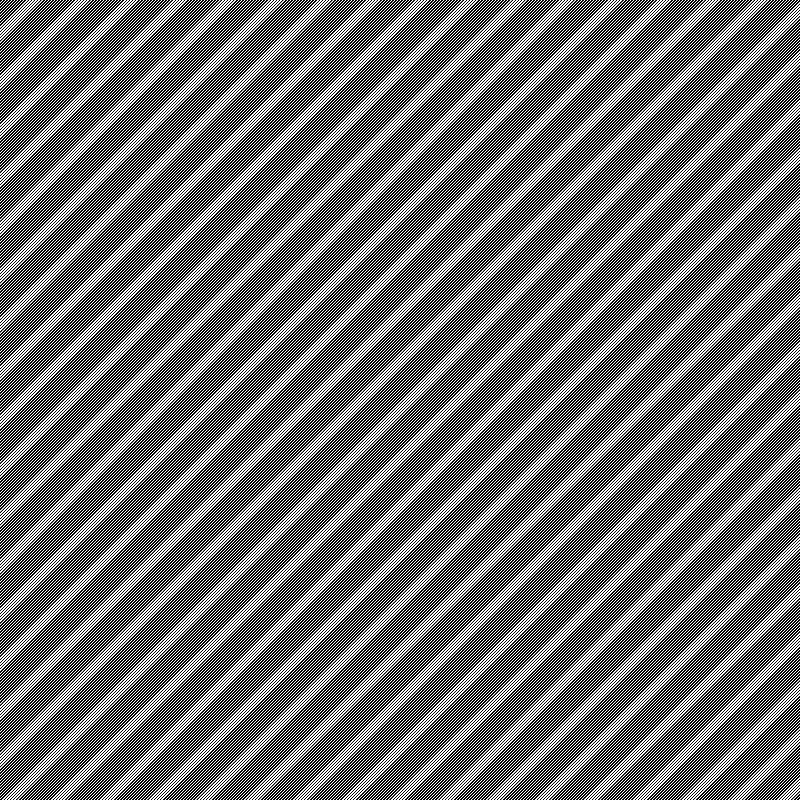

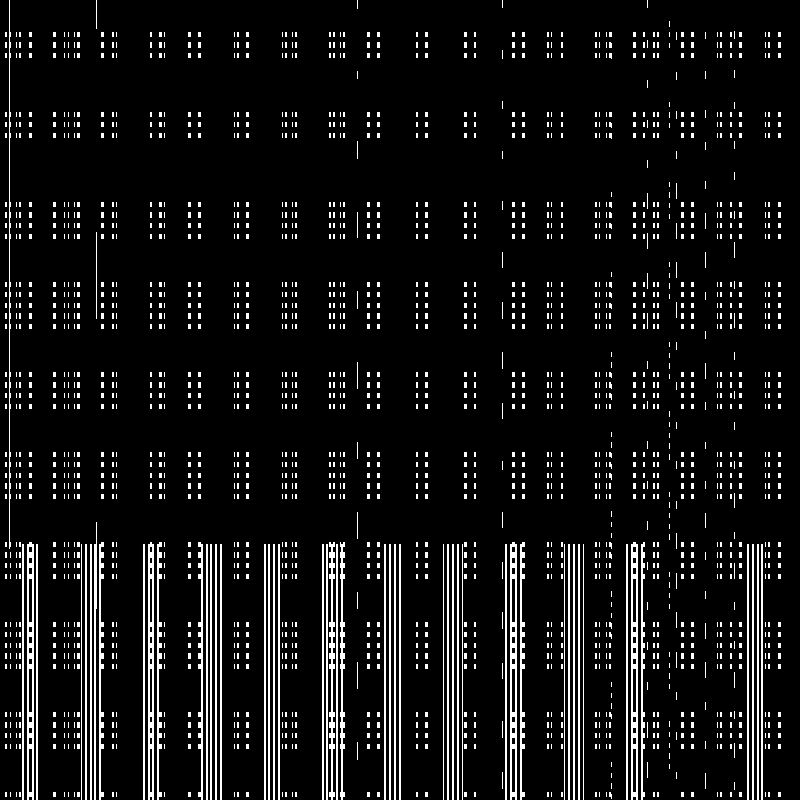

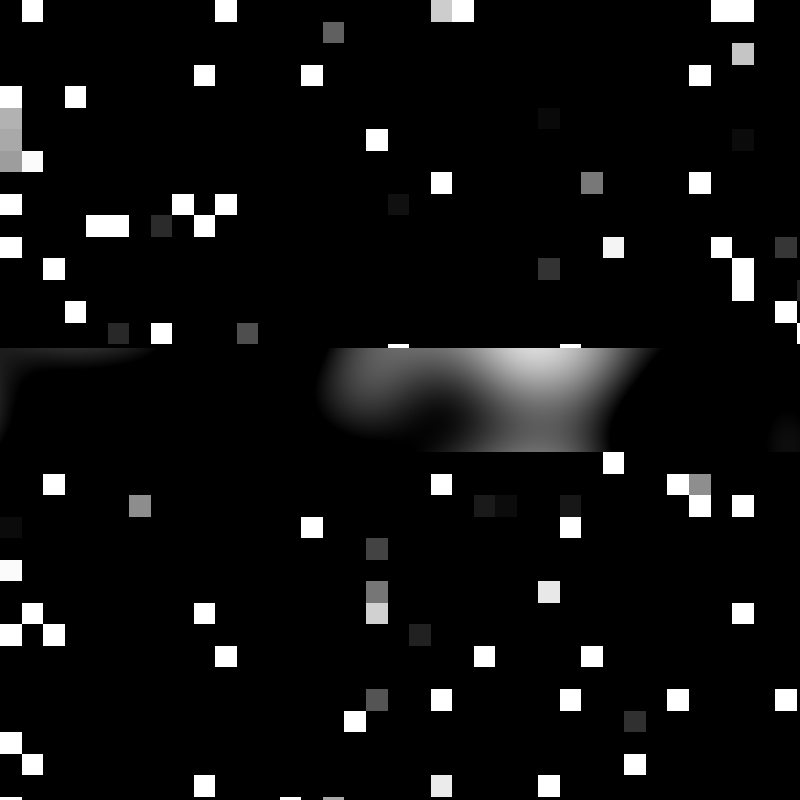

Instead of rearranging the stones, which I have fixed, everything else is by way of chance. Original physical walls, imaginary walls, p5js raked sands, trees beyond walls, our visions we see with our mind not our eyes, elicit meditation on screen.

Time to meditate and heal.

Press 1 to save png. Tested on chrome+firefox, please be patient, it might take 10 seconds or more to render. Preview images are compressed.

Private release at 50tz. Public release starting at 100tz. Prices are subject to change at any price above 100tz.

Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Notes on Ryoanji:

Like any work of art, the artistic garden of Ryōan-ji is also open to interpretation into possible meanings. Different theories put forward about what the garden is supposed to represent. Garden historian Gunter Nitschke wrote: "The garden at Ryōan-ji does not symbolize anything, or more precisely, to avoid any misunderstanding, the garden of Ryōan-ji does not symbolize, nor does it have the value of reproducing a natural beauty that one can find in the real or imaginary world. I consider it to be an abstract composition of objects in space, a composition whose function is to incite “meditation”.

In the science journal Nature, Gert van Tonder and Michael Lyons analyze the rock garden by generating a model of shape analysis. Using this model, they showed that the empty space of the garden is implicitly structured, and is aligned with the temple's architecture, where the axis of symmetry passes close to the center of the main hall. The implicit structure of the garden is designed to appeal to the viewer's unconscious visual sensitivity to axial-symmetry skeletons of stimulus shapes. And found that imposing a random perturbation of the locations of individual rock features destroyed the special characteristics.

BUT this is not how John Cage views the garden.

Cage first visited the Ryoanji Temple and rock garden in 1962, during a concert tour of Japan with David Tudor, Toshi Ichiyanagi, and Yoko Ono. Measuring 30 x 10 meters, the garden consists of carefully raked white pebbles with 15 rocks arranged.

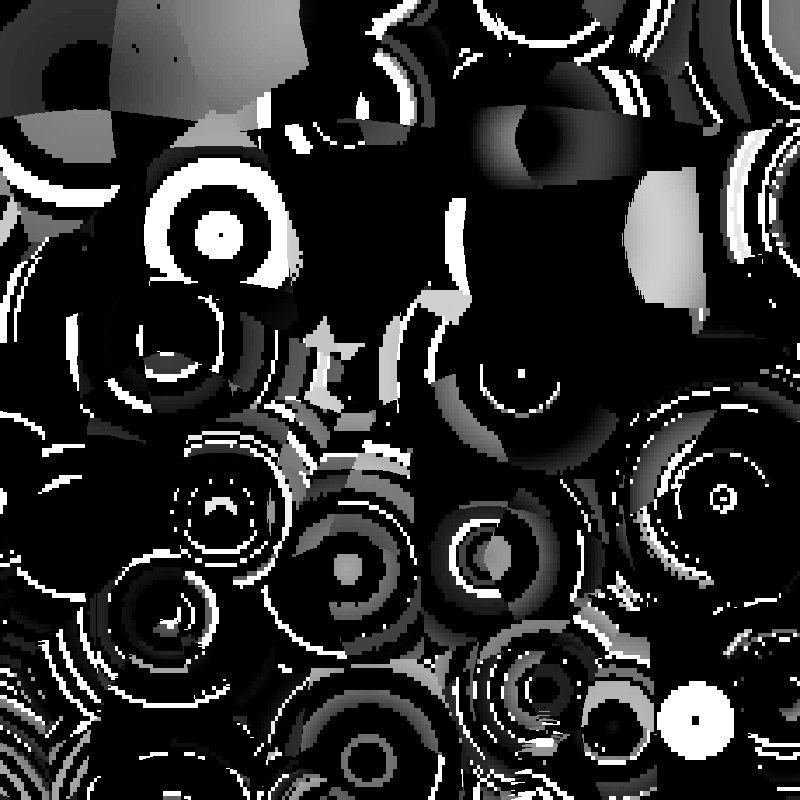

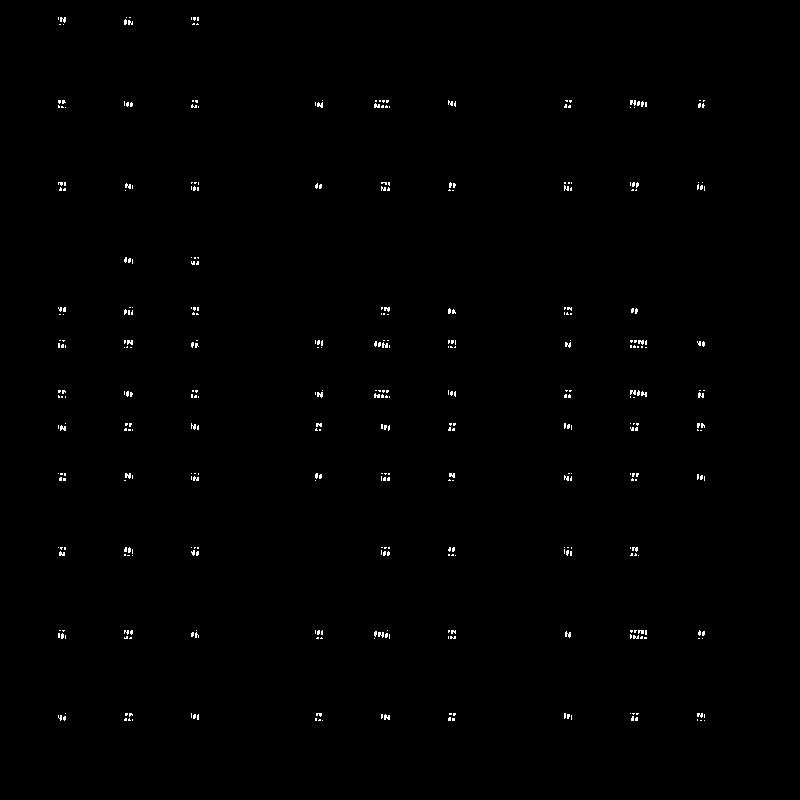

In 1982, when Cage was commissioned to design the cover for a book to be published by Editions Ryôan-ji, as with all of his late artistic endeavors, he developed processes of chance-controlled creation, consulting the coin oracle of the I Ching and later computer-generating randomized numbers, reducing the subjective aspects of both composition and performance. Cage placed a selection of stones from his collection, positioned by chance operations, on the plate and traced their outlines. Each print’s title dictated the number of times he outlined each stone. For example, the dense, allover mesh of marks in R3 (where R=Ryoanji) represents fifteen stones, each traced 225 times to produce a total of 3,375 stone silhouettes (15 x 15 x 15 equals 3,375).

Over a period of ten years, the last decade of his life, Cage devoted himself to drawings addressing the aesthetic order of the complex yet simple that is revered in Japan as a perfect depiction of nature (with Buddhism or Zen influence). “Ryoanji” compositions focus on how John Cage expressed his ideas and the garden’s sensibility in both his audio and visual interpretations.

If meditation is of the mind, then generation is a meditation of the machine. Generations of my coding asserted or not, of the gardens, ease mediations, in a sense of the infiniteness and impermanence of the generated.

Given the reality of physics, rearrangements of Ryoanji is not feasible. As John Cage composed his Ryonaji with chance, pencil and paper. I recompose Ryoanji exploring the limits and boundary of generative art in code. An explorations of meditation.

Instead of rearranging the stones, which I have fixed, everything else is by way of chance. Original physical walls, imaginary walls, p5js raked sands, trees beyond walls, our visions we see with our mind not our eyes, elicit meditation on screen.

Time to meditate and heal.

Press 1 to save png. Tested on chrome+firefox, please be patient, it might take 10 seconds or more to render. Preview images are compressed.

Private release at 50tz. Public release starting at 100tz. Prices are subject to change at any price above 100tz.

Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Notes on Ryoanji:

Like any work of art, the artistic garden of Ryōan-ji is also open to interpretation into possible meanings. Different theories put forward about what the garden is supposed to represent. Garden historian Gunter Nitschke wrote: "The garden at Ryōan-ji does not symbolize anything, or more precisely, to avoid any misunderstanding, the garden of Ryōan-ji does not symbolize, nor does it have the value of reproducing a natural beauty that one can find in the real or imaginary world. I consider it to be an abstract composition of objects in space, a composition whose function is to incite “meditation”.

In the science journal Nature, Gert van Tonder and Michael Lyons analyze the rock garden by generating a model of shape analysis. Using this model, they showed that the empty space of the garden is implicitly structured, and is aligned with the temple's architecture, where the axis of symmetry passes close to the center of the main hall. The implicit structure of the garden is designed to appeal to the viewer's unconscious visual sensitivity to axial-symmetry skeletons of stimulus shapes. And found that imposing a random perturbation of the locations of individual rock features destroyed the special characteristics.

BUT this is not how John Cage views the garden.

Cage first visited the Ryoanji Temple and rock garden in 1962, during a concert tour of Japan with David Tudor, Toshi Ichiyanagi, and Yoko Ono. Measuring 30 x 10 meters, the garden consists of carefully raked white pebbles with 15 rocks arranged.

In 1982, when Cage was commissioned to design the cover for a book to be published by Editions Ryôan-ji, as with all of his late artistic endeavors, he developed processes of chance-controlled creation, consulting the coin oracle of the I Ching and later computer-generating randomized numbers, reducing the subjective aspects of both composition and performance. Cage placed a selection of stones from his collection, positioned by chance operations, on the plate and traced their outlines. Each print’s title dictated the number of times he outlined each stone. For example, the dense, allover mesh of marks in R3 (where R=Ryoanji) represents fifteen stones, each traced 225 times to produce a total of 3,375 stone silhouettes (15 x 15 x 15 equals 3,375).

Over a period of ten years, the last decade of his life, Cage devoted himself to drawings addressing the aesthetic order of the complex yet simple that is revered in Japan as a perfect depiction of nature (with Buddhism or Zen influence). “Ryoanji” compositions focus on how John Cage expressed his ideas and the garden’s sensibility in both his audio and visual interpretations.

Filters

Features

No features

Listings